Recently, a research team surveyed UC tenure-track teaching faculty (which I’ll refer to as tenure-track teaching professors – or T3Ps to align with the spirit of this network”) to better understand support structures and obstacles to success in research, teaching, and service activities—the three pillars of the UC system. Because of my position as an educational researcher who studies faculty models, I was given exclusive access to the survey and its results. A number of survey items piqued my interest, but one in particular really made me start to think about T3P trajectories.

I’ve always found the T3P position in the UC system to be relatively unique and specialized. Teaching faculty exist elsewhere, of course, but in this specific system, they are folks who are uniquely passionate about teaching within their discipline (yes, that’s right—actually excited to teach introductory biology to thousands of undergraduates, for example) while also being interested in understanding—and empirically studying—how students learn. I’ve often wondered things like how did UC T3Ps stumble upon this particular career path? What were they searching for in a job?

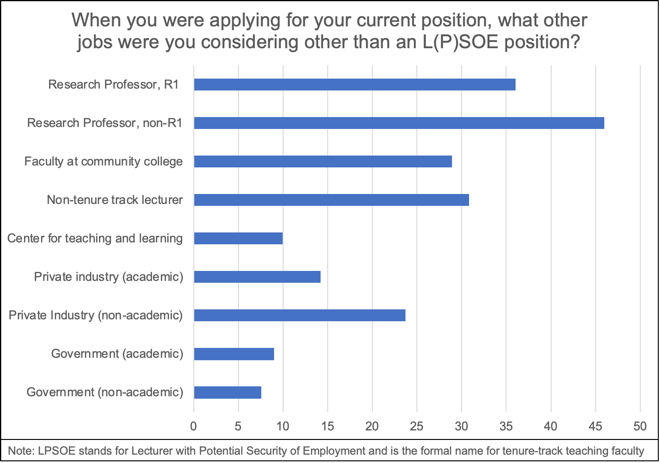

Reviewing the survey seemed like a good first step in answering these questions. Specifically, the survey asked faculty to describe the different types of jobs they applied to during their search process that landed them a UC teaching faculty position. As shown in Figure 1, survey participants had considered a number of other opportunities during their search. Faculty considered tenure-track research faculty at both R1 (36%) and non R1 (46%) universities; many of them also considered becoming community college faculty or non-tenure-track lecturers. Interestingly, 24% of survey participants considered non-academic positions in the private industry as well.

Overall, these responses seemed to point to the prioritization of teaching over research but did not paint the more nuanced picture that I wanted. I decided to ask for more information from T3Ps, and from their responses, a few salient themes emerged.

First, as the survey data suggested, UC T3Ps were intentional about finding jobs that prioritized teaching. A number of faculty members had worked at or pursued positions at a community college, positions at liberal arts colleges, and positions at other colleges serving only undergraduate students. Many expressed a desire to work with students in foundational STEM courses; further, their prioritization of teaching stemmed less from a desire to be a sage on a stage flaunting Nobel-prize-winning research and more from a desire to prepare students to be successful learners. Their responses made it clear that teaching faculty used the classroom as a place to make an impact by building and maintaining strong student-instructor relationships. As one teaching faculty member put it simply, “Making and maintaining connections with students is the best part of being an educator.”

Also important to note: it became clear to me that their efforts to make connections were often motivated by personal experiences. One faculty member shared how an office hours visit changed his educational trajectory in college because of the support he received from his instructor. The instructor continued to help him navigate college by encouraging him to take more biology courses, join a lab, and pursue a Ph.D. in Biology. Now he too wants to be the kind of role model that helps shape students’ paths.

Second, UC T3Ps were intentional about finding opportunities that positioned them to help colleagues and future faculty (graduate students) improve their teaching and pedagogy. A number of them considered themselves experts in the field of teaching and learning—further, some were in postdoctoral positions studying discipline-based education research prior to obtaining a teaching faculty position—and shared a desire to serve as agents of change within their departments as well as in a larger academic sense. In their responses to my questions, faculty wrote enthusiastically about the number of different opportunities they had to coordinate professional development workshops about teaching and work with faculty directly on curriculum development. One faculty member stated, “What I enjoy most about this position is working at the intersection of pedagogical and institutional change and seeing how these transformations influence student success. The best part of being an educator is making and sustaining connections with students.”

I started to think about how these professors’ desire to serve as agents of change was represented in their motivation to find a position that let them participate in both teaching and learning. Even though we often hear about faculty avoiding evidence-based teaching practices, for teaching faculty, it is quite the opposite; they are eager and enthusiastic about using their own classrooms for investigating ways to improve student success and sharing their findings with the entire community of educators, including both teaching and research faculty. As one faculty member stated, “I love challenging my colleagues to think outside of the box of what they’ve done with their teaching—and back up new pedagogical ideas with data that I’ve personally collected in my classes!”

My conclusion: UC T3Ps didn’t stumble upon their specialized position. Instead, they were intentional about their search, guided by a single northern light–improving the learning experiences of students in college. I’m left wanting to learn more about them, though. What types of teaching practices do they use in their courses? What advice do they have for Ph.D. students who hope to travel the same path? What types of professional development opportunities are provided to these faculty? How do they serve as change agents in their respective departments? What types of changes have they seen in terms of student success? Stay tuned, as we will tackle these questions in future posts.

If you are interested in contributing to Community Reflections and writing a blog post, please reach out to us at UCTPN@uci.edu.